Rome keeps its worst stories behind very pretty walls.

Few are prettier, or worse, than the tale of Giulia Tofana, Acqua Tofana, and the women who reached for poison when every other door was locked.

On our Rome’s Dark Side – Ghosts & Legends tour (also known, less delicately, as our Rome Ghost Tour), we stop at a crooked little building on the corner of Via dei Banchi Vecchi and Via di Monserrato, a few steps from Vicolo della Moretta.

Today it is a cheerful gelateria handing out pistachio and stracciatella. In the 1600s, the same corner was part of a very different menu.

From here, a real poison ring once operated in this tight little wedge of streets. Apothecaries, back rooms, quiet exchanges. Vials that turned dinners into death sentences and trapped wives into widows.

The nearby Vicolo della Moretta literally means “alley of the little dark girl” – one of those suspiciously specific Roman street names that feels less like a description and more like a clue to a story we have mostly lost.

The interesting part is not how these women did what they did. It is why so many others decided the risk was worth it.

The corner of Via di Monserrato & Via dei Banchi Vecchi, where Giulia, Girolama and their ring ran their operation

Giulia Tofana did not invent murder by bottle. She refined the family business.

In Palermo, her mother Thofania d’Adamo, an apothecary’s widow, was tried and executed in 1633 for supplying poison to wives who wanted their husbands gone. Whatever she was selling was probably an early version of what Rome would later call Acqua Tofana.

Giulia grew up among herbs, oils and face waters that could soothe a headache or quietly erase the person responsible for it. Beauty, medicine and homicide shared counter space.

By the time she steps into the Roman record, she is a widow herself. No court document proves she tested the recipe on her own husband, but the timing is neat enough that Roman storytellers have been raising an eyebrow about it ever since.

She moved north to the papal city, set herself up as a cosmetician in the dense streets around today’s Via di Monserrato and Via Giulia, and picked up where the family trade had left off. Creams for the skin. Waters for the face. And for certain clients, something stronger.

Giulia’s masterpiece was Acqua Tofana, a clear, nearly flavourless liquid thought to be based on arsenic, probably blended with other toxic favourites like lead and possibly belladonna.

On the shelf, it behaved itself. It could be:

•a cosmetic “manna” to brighten and smooth the skin

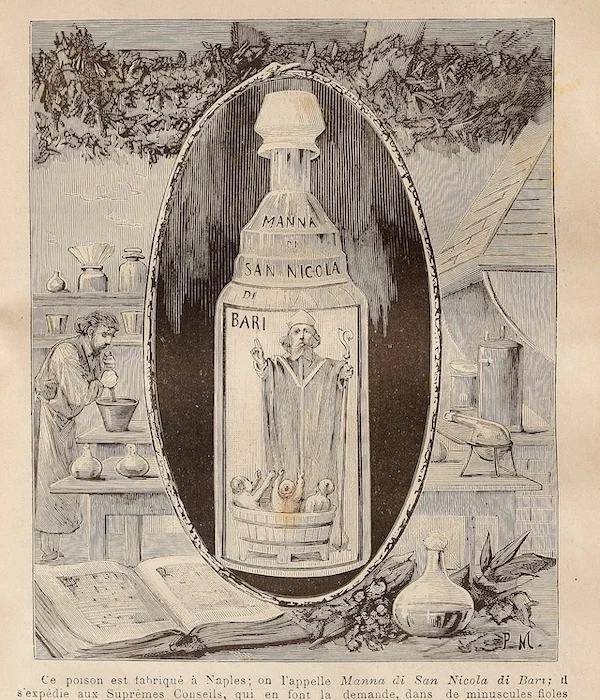

•a devotional product labelled Manna of Saint Nicholas of Bari, echoing the genuine healing oil associated with the saint’s shrine

In the kitchen, it had a different vocation.

A few drops stirred into soup or wine over days made a husband quietly sick. No dramatic collapse into the plate. Just a steady decline that looked convincingly like a natural illness.

Doctors frowned at mysterious fevers. Priests talked about the state of the soul. Wives cried on cue and dabbed their eyes with admirable technique.

At the end, there was:

Stories say Giulia and her circle even offered coaching. When to call the doctor. How to ask for an autopsy without sounding too enthusiastic. How much mourning was just enough.

Poison, with customer support.

Portrait of a bottle of Tofana water bearing the image of Saint Nicholas of Bari (work by Pierre Méjanel)

To understand why Acqua Tofana spread through 17th-century Rome, the ingredients are almost beside the point. The real poison was the system it was poured into.

In the papal city:

So when guests on Rome’s Dark Side – Ghosts & Legends tour ask why these women didn’t simply walk away, the answer is blunt and unsatisfying. They couldn’t.

Their options narrowed to two. Stay and endure. Or gamble everything on escape.

Giulia quietly offered a third: stay, and change who does not survive.

That does not make her a saint. It does stop the city around her from looking innocent, which is closer to the truth.

Giulia did not run this alone, and she did not just inherit a recipe. She built a structure and then left it in new hands.

Her daughter (or stepdaughter – sources disagree) and protégée Girolama Spara (often written Gironima Spana) emerges later as the central figure in what became the Spana Prosecution, the huge poison trial that shook Rome in 1659.

In the records she appears as Gironima Spana, but later tellings sometimes call her Girolama Spera. In Italian, spera means “she hopes” and shares a root with speranza, “hope” – a little too perfect for a woman who, for many Roman wives, was exactly that: a last, dangerous hope in human form.

And then there is that nearby Vicolo della Moretta, the “alley of the little dark girl”, right by the corner where the apothecary once stood and where the gelateria now scoops ice cream. Some storytellers like to imagine it nods to a young, darker-skinned Sicilian woman in the area, perhaps someone like Girolama herself. It is speculation, nothing more, but Rome has never been shy about turning coincidences into folklore.

By the time the authorities focused on Girolama, Giulia Tofana was probably already dead. Some sources say she slipped away quietly around 1651, leaving the Roman operation to her successor.

Girolama managed a web of female dealers who sold Acqua Tofana and similar preparations disguised as cosmetics and medicines to desperate wives across the city. Part beauty culture, part underground resistance, part very illegal business plan.

Eventually, someone talked. The network collapsed under interrogation. Girolama and several key associates were arrested, tortured and condemned. The leaders were hanged in Campo de’ Fiori, while many clients, especially noblewomen, were sentenced to banishment, public shaming or lifelong imprisonment in harsh convent-prisons.

Later storytellers enjoyed saying these women were “walled up alive”. The records suggest something only slightly less theatrical: grim, lifelong confinement rather than literal brickwork.

It is not hard to see why Giulia Tofana sometimes gets treated as a kind of feminist icon.

Her circle served women stuck in marriages where:

Acqua Tofana gave those women control over the one thing their husbands took absolutely for granted: that their wives would still be alive at breakfast.

In a world where sermons raged against sin but institutions looked away from bruises, people like Giulia, Thofania and Girolama were often the only ones offering an answer to certain kinds of suffering. The answer was expensive and final, but it existed.

If heroism means doing the right thing inside a just system, they fail immediately. If it means acting when the system itself is rotten, their story starts to feel uncomfortably necessary.

Then there is the other side. The one that looks less like resistance and more like a business model.

Acqua Tofana did not examine anyone’s conscience. Not every man who died from it was a documented monster. Some were violent, some indifferent, some simply unloved. The poison treated them all the same.

Giulia and her successors:

When the operation finally imploded during the Spana Prosecution, the collateral damage was severe. Executions in Campo de’ Fiori. Harsh sentences in convent-prisons. A new strain of male paranoia every time the soup tasted slightly off.

Yes, the system was abusive. Yes, patriarchy was alive and well. But the network also professionalised murder. Whatever else they were, they were not uncomplicated liberators.

Like most of the stories we tell on our Rome Ghost Tour, the saga of Giulia Tofana is stitched together from court files, pamphlets and a few centuries of enthusiastic retelling. Some parts are solid. Others are more… flexible.

A few things to keep in mind:

So when we talk about her on the street at night, we keep the tone honest. Part documented history, part moral panic, part urban legend polished over time.

If haunted Rome has a house blend, that is it.

So what was Giulia Tofana, really?

If Rome had given women legal protection, financial independence and a way to leave abusive marriages, Giulia Tofana might be a forgotten name on an old shop sign, remembered only as a maker of creams and perfumes in Palermo or Rome.

Instead, her name was whispered whenever husbands fell mysteriously ill, invoked with every suspicious cough, and muttered by patriarchy whenever it started eyeing its own dinner with concern.

Calling her a pure hero is dishonest. Calling her a simple villain is too kind to everyone else.

She is better read as evidence. A symptom in human form of a society that preferred dead husbands to living, inconvenient wives.

If you want this story where it belongs, on stone instead of a screen, you will find it on our Rome’s Dark Side – Ghosts & Legends evening walk, our original Rome Ghost Tour through the darker corners of the historic centre.

We take you to:

There are no costumes, no fake blood and no jump scares. Just real history, bad decisions and the occasional bottle of “holy water” that was anything but.

If you want to decide for yourself whether Giulia Tofana was a hero, a villain, or simply the most practical person in the room, the Roman night on the corner of Via di Monserrato is an excellent place to start.

Visit the site with us on our Rome’s Dark Side Tour.

Giulia Tofana was a 17th-century poisoner who operated between Palermo and Rome, building on a family trade that began with her mother, Thofania d’Adamo. She sold cosmetics and “remedies” on the surface, and Acqua Tofana to selected clients underneath. She never needed to kill anyone herself; she equipped other women to do it quietly at home.

Acqua Tofana was a liquid poison sold to women who wanted their husbands dead and their hands technically clean. It was clear, almost tasteless, and disguised as face water or holy “manna” linked to Saint Nicholas of Bari. In a city obsessed with appearances, it was the perfect murder weapon: invisible and respectable.

Yes. Acqua Tofana wasn’t just a spooky story; it appears in trial records, confessions and contemporary reports from 17th-century Italy. The recipe itself is lost, but the panic, executions and crackdowns it caused were very real. Rome does not hang people over a rumour alone… most of the time.

Most historians agree Acqua Tofana was primarily arsenic-based, probably mixed with other toxic compounds like lead and possibly belladonna. The goal was simple: a clear, dissolvable liquid that blended into food and wine without changing the taste. Think less “mystical potion”, more “highly efficient early-modern chemistry”.

Acqua Tofana worked slowly, which was the whole point. A few drops added to meals over several days made the victim fall ill with symptoms that looked like a natural disease – weakness, stomach pain, gradual wasting. Doctors blamed ordinary illness, priests prepared the soul, and the widow cried on cue while the poison quietly did its job.

Giulia Tofana and her successors are most closely linked to the area around Via di Monserrato, Via dei Banchi Vecchi, and Vicolo della Moretta in the historic centre – the same corner where a gelateria stands today. The later fallout of the poison network also touches Campo de’ Fiori, where key figures like Girolama Spana were executed. On our Rome’s Dark Side – Ghosts & Legends tour, we walk through these streets and stand on that corner, because this isn’t just a legend; it has an address.

Discover the hidden tales of history – the ones you won’t hear in your history class